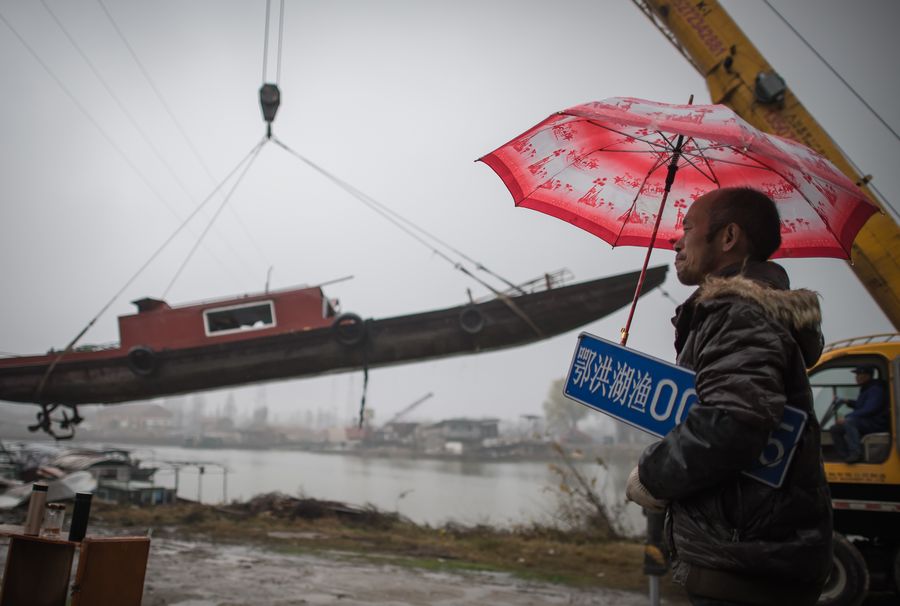

Xia Mingxing, a fisherman from Changjiangbulao Village, keeps his eyes on a suspended fishing boat with his boat license plate in hand in Hubei Province, central China, on Dec. 25, 2019. (Xinhua/Xiao Yijiu)

Nearly 280,000 fishermen have dropped fishing as China pushes for a 10-year fishing moratorium on Yangtze River.

by Xinhua writers Yao Yuan, Wang Xian and Yue Wenwan

WUHAN, Jan. 1 (Xinhua) -- On a rainy afternoon in late December, a group of ex-fishermen came to the bank of the Yangtze River to bid farewell to their longtime workmates.

They stood in solemn silence as an excavator dismantled one fishing boat after another in deafening roars. Xia Mingxing, one boat owner, failed to conceal his tears.

"It's so hard to part with the boat that has been with my family for so many years, but I know for the environmental greater good, I have to let it go," said the 57-year-old villager in Hubei Province.

Xia is from the village of Changjiangbulao, which in Chinese means "fishing in the Yangtze," a term that will likely retreat into history as China pushes for a 10-year fishing moratorium on Asia's longest river.

Facing depleting fish stocks and degrading biodiversity in the Yangtze, the Chinese government has decided to step up the fishing bans and pollution control measures. Starting on Jan. 1, 2020, the ban will be observed in 332 conservation areas along the waterway, before expanding to the entire river and its main tributaries in 2021.

The historic moratorium will last for a decade, grinding an estimated 110,000 fishing boats and driving nearly 280,000 fishermen ashore.

For Xia's village, located in a national reserve for white-finned dolphins, it marks the end of an era of living on water and relying on nature's bounty. All its 56 families have dropped fishing after receiving at least 60,000 yuan (8,590 U.S. dollars) per household in government compensations. While most young fishermen left for jobs in other cities, the older ones live by odd jobs and government pensions.

Ex-fisherman Xu Bao'an (1st R) works in a shoe factory in central China's Hubei Province, on Dec. 26, 2019. (Xinhua/Xiao Yijiu)

Xu Bao'an from the nearby Honghu Village quit fishing in 2017 and now works in a local shoe factory.

"I'm satisfied with my life now, with stable incomes and a job not far away from home," Xu said. "There were hard times at the start of the transition, but we knew it was in the best interest of the Yangtze and future generations."

Conversationalists hail the fishing moratorium as a crucial step to stem the river's biodiversity freefall. In recent decades, the ancient aquatic paradise has seen its iconic white-finned dolphins declared functionally extinct, and another freshwater mammal -- the finless porpoise -- is teetering on the brink of extinction due to pollution, overfishing, busy river traffic and other human-induced changes.

Even the river's more mundane denizens are struggling. Official surveys suggest the fry of four common Yangtze fish (herring, grass carp, silver carp and bighead carp) have reduced by 90 percent from the 1950s levels.

The shrinking fish stocks prompted fishermen to employ denser nets and illegal means like electrocuting the water, which further exacerbated the environmental woes.

"Fishermen were caught in a vicious circle -- the more they fish, the poorer they become because of the worsening environment," said Cao Wenxuan, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Since 2003, China has put in place a seasonal fishing ban, leaving Yangtze fishermen without work for three months each year. The ban expanded to four months in 2016, but Cao, who has called for a decade-long moratorium since 2006, said longer periods are needed to allow most Yangtze fish to thrive for 2-3 generations so as to restore populations.

"Moreover, fishing in the Yangtze produces less than 1 percent of China's total aquatic products. The fishermen's withdrawal from the river will have minimal impacts on China's fishing industry," said the ichthyologist.

However, persuading fishermen to forego their ancestral line of work and life on boats was not easy.

"Some people have seasickness, but we have land sickness," said 55-year-old Long Kaiyun, who was reluctant to move out of his boat in Nanxian County, Hunan Province. "The government allocated houses for us, but we rarely spend nights there. When we sleep in beds, we feel as if the floor is wobbling."

Luoshan Town, which administers the villages of Changjiangbulao and Honghu, faced the same reluctance. To facilitate the resettlement, which began in 2016, local officials surveyed fishermen's reemployment wishes and arranged relevant skill training.

"We've opened training courses on welding, computer operation and aquaculture. And every year, we held four to five job fairs for the fishermen," said Yue Guanhui, Party chief of Luoshan.

For older fishermen who lack skills or motivation to work in companies and factories, plans are also afoot.

"These fishermen are familiar with water and have special feelings for the Yangtze River. We plan to set up ecological positions and transform them into fish protectors and river patrollers," Yue said. ■